“The future of perfumery is in the hands of chemists… We’ll have to rely on the chemists to find new chemicals if we are to make new and original accords.” – Ernest Beaux

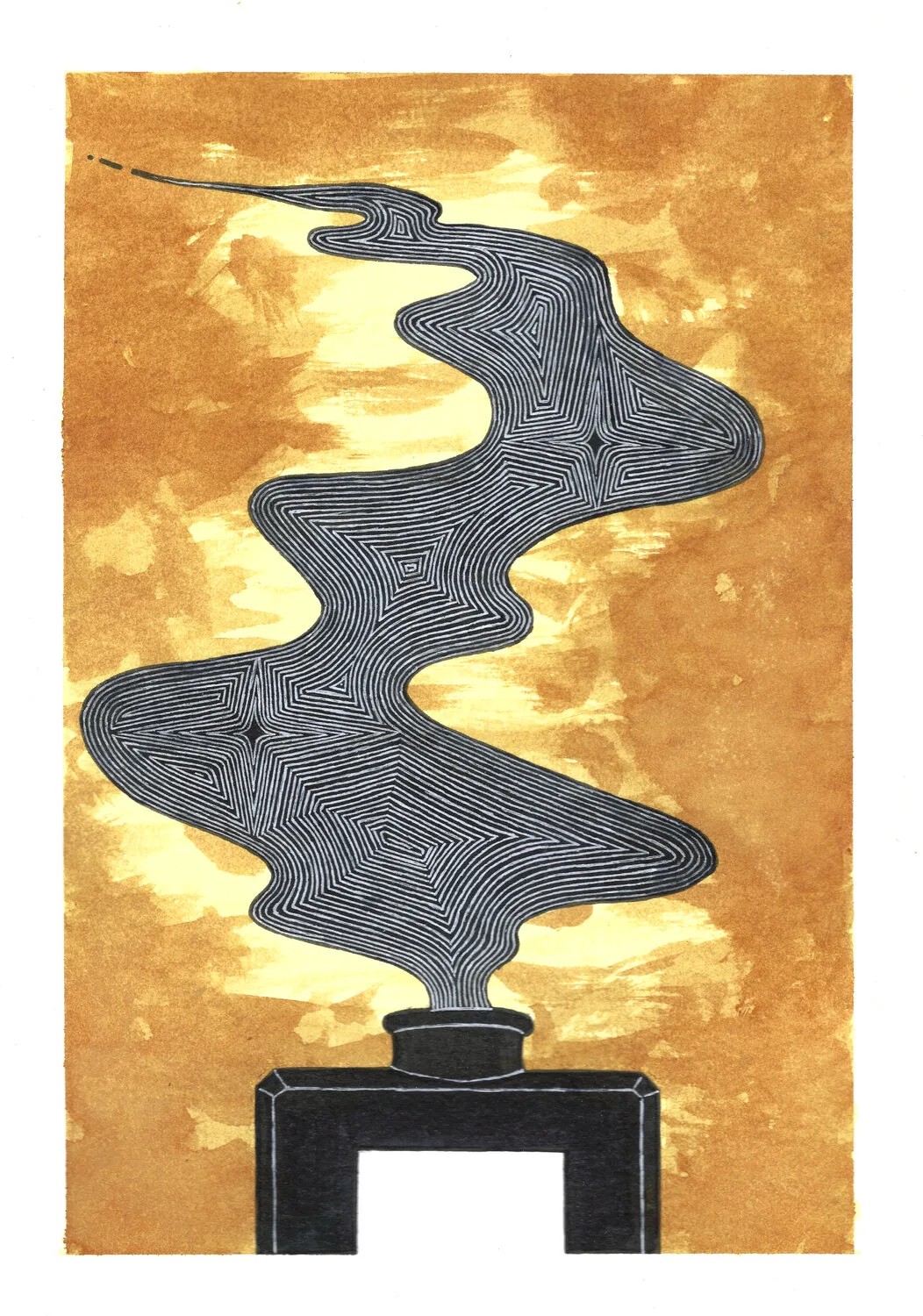

The composition of a masterful fragrance is one that requires a keen understanding in the art of balance. There is a very fine line between synthetic and natural ingredients that a “nose” must walk, like an acrobat walking the tightrope high in the air. Too far on one side, and the fragrance will smell harsh and overly bright, too far on the other side and it will miss the flair a true work of art requires.

In this way, the art of parfumerie goes hand in hand with chemistry, and is often at the forefront of new aromatic compounds. It cannot be overstated just how impactful and important new discoveries can be to the field. Quelques Fleurs, No. 5, No. 22, Arpège, Rive Gauche, First, Liu, and many others owe their existence and popularity to the discovery of one of the most influential note families of all time, aldehydes.

But, what are aldehydes exactly, and more importantly, what do they smell like? In this article, let’s explore the history, science, and, of course, scent profiles of one of the most prolific note families in fragrance history.

If you prefer short-form videos, click here to watch my TikTok video on this topic.

A Dazzling History

The art of parfumerie is one that is thousands of years old. From Ancient Rome to the Ancient Middle Eastern civilizations, making scented oils and parfums was, and is, something humans put value into. For centuries, these craftsmen would only have access to naturally derived ingredients found either in the local region, or imported (at great expense) from more distant lands.

The largest revolution in parfumerie would only come on the back of another revolution, the founding and research into the field of organic chemistry.

A relatively recent offshoot of chemistry, organic chemists research organic compounds to study their structures, qualities, and determine their structural formula. Plastics, lubricants, pharmaceuticals, and even dyes are all products produced by this field.

In 1835, Justus von Liebig, one of the founding fathers of organic chemistry, first proposed the name “aldehyde” after his research into the structures. Following his research, other aldehydes were discovered and noted. In 1903, George Auguste Darzens, a Russian-born French chemist, first synthesized to produce them.

But how did they come to be used in fragrances?

From Science to Art

There is a common misconception that Chanel’s legendary No. 5 (1921) was the first fragrance on the market to make use of aldehydes. Although No. 5 was a groundbreaking fragrance in many ways, it was not the first fragrance to use aldehydes in its composition.

Instead, from my research, all sources point to a fragrance named Rêve d’Or, created in 1905 by Louis Armingeat.

As an aside, my research has not made it clear whether or not the Rêve d’Or from 1905 is the same as L.T. Piver’s Rêve d’Or. The LTP fragrance was originally made in 1889, and is attributed to Armingeat in the Osmotheque. The only evidence I have found of a reformulation occurred in 1925, not one in 1905. However, due to the attribution of the composition to Armingeat, and the fact that Auguste Georges Darzens worked for L.T. Piver from 1897-1920, it is likely the same fragrance.

Directly following Rêve d’Or, in 1906 Guerlain would release Après l’Ondée, featuring the first use of Anisic Aldehyde. 1912 would see the release of Quelques Fleurs, using aldehyde notes to breathe life into its novel floral bouquet.

The prominence of aldehyde usage in parfumerie would happen after the smash success of Chanel’s No. 5 in 1921. Although not the first to make use of them, No. 5 was the first to make them a prominent note of the composition, an “overdose” of the note family.

By 1922, aldehydes were one of the most sought after and prominent notes in a perfumers collection. But what made them so intoxicating?

A Sparkling Sensation

When reviews, collectors, and regular fragrance consumers speak about aldehydes, typically the descriptors are fairly simple. The note is often described as soapy, clean, fresh, waxy, and/or synthetic. This is only partially correct. Although some aldehydes can have this scent profile, perfumers have access to a variety from this note family, with each one going its own special direction. Additionally, the term “aldehyde” is a catchall term for a wide range of organic compounds. The most common used by perfumers are the aliphatic aldehydes, however there are also aromatic aldehydes perfumers use, as well as a few outliers. Let’s explore some of the more common ones in more depth.

| Alphatic Aldehydes | |

|---|---|

| C7 (Heptanal) | Green, fresh, and herbal. Also possesses a slightly rancid fruit quality. |

| C8 (Octanal) | Fruit-like and citrusy, often associated with oranges and orange peels. Slightly waxy as well. |

| C9 (Nonanal) | Depending on dilution, can either smell very fresh and clean, or green and rosy. Often added to floral bouquets to make the floral notes “bloom.” |

| C10 (Decanal) | Intensely smells of oranges and citrus. Slightly sweet. |

| C11 (unsaturated) | The standard “aldehydic” scent. Clean, fresh, slightly more on the citrusy side. |

| C11 (saturated) | Similar to unsaturated C11, but slightly more on the floral side, with a hint of a fruity note. |

| C12 (Lauric) | Slightly sweet, fresh, and clean floral. Reminiscent of lilac. |

| C12 (MNA) | Floral, metallic, fresh, with a slightly mossy kick. |

| C13 (Tridecanal) | Fresh, clean, soapy, with a slight grapefruit note. |

| Outliers | (Technically Lactonics, labelled as Alphatics) |

|---|---|

| C14 | Widely known and used for its peach profile. Famously used in Guerlain’s Mitsouko. |

| C16 | Tastes and smells of strawberries, as such given the nickname “strawberry aldehyde.” |

| C18 | Sweet with a touch of coconut, often used in a variety of floral applications. |

| Aromatic Aldehydes | |

|---|---|

| Anisealdehyde | Floral, sweet, strongly carries the note of licorice and hawthorn. |

| Benzaldehyde | Smells of bitter almonds and cherries. |

| Cinnamaldehyde | Smells warm and spicy, like cinnamon. |

| Cuminaldehyde | Spicy with cumin-like qualities. |

| Vanillin | Intensely smells of vanilla, found in almost all vanilla fragrances. |

The Great Disappearing Act

For the decades following the launch and popularity of No. 5, the classic “aldehydic” note remained an ever present part of a large amount of new fragrance releases. As the years progressed, and consumers’ preferences shifted, the note’s popularity waned, but aldehydes never stopped being used.

Outside of this list, a vast variety of aldehydes exist with their own qualities and traits, many still used to this day. Perfumers will always use aldehydes to add a spark to their compositions, and often pair it with the new crop of synthetic aroma-chemicals that gain popularity.

A new crop that might not exist had it not been for the early pioneers of this new, and exciting scent family.

Leave a Reply